Some say that we shall never know and that to the gods we are like flies that the boys kill on a summer day, and some say, on the contrary, that the very sparrows do not lose a feather that has not been brushed away by the finger of God.

Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

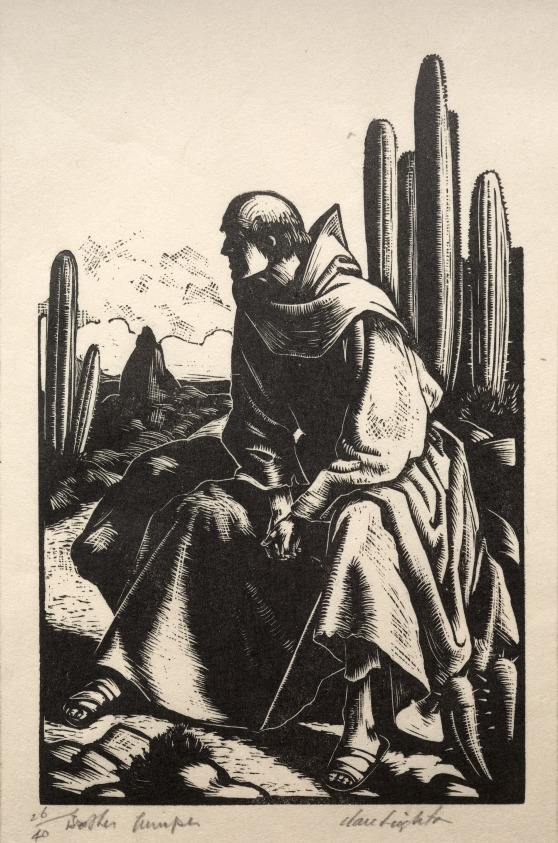

The Bridge of San Luis Rey is a novella by Thornton Wilder that opens with the bridge of San Luis Rey collapsing and sending five people to their deaths. The single witness to this event, Brother Juniper, decides at that moment to track down information on the lives of all of these people in order to prove scientifically the theological point that certain kinds of lives lead to certain kinds of deaths. He looks at the lives of Doña María (the Marquesa de Montmeyor) and Pepita, Esteban, and Uncle Pio and Jaime.

And I, who claim to know so much more, isn’t it possible that even I have missed the spring within the spring?

Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

Wilder weaves the tales of these characters together, tying them to each other through commonalities of place and acquaintance. The characters in the novella dance around each other, in and out of each others’ lives, sometimes directly and sometimes only barely, as through the friend of a friend.

She was one of those persons who have allowed their lives to be gnawed away because they have fallen in love with an idea several centuries before its appointed appearance in the history of civilization. She hurled herself against the obstinacy of her time win her desire to attach a little dignity to women.

Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

Overall: the writing in this book is absolutely phenomenal. It is lyrical, simple, terse, and elegant all at the same time. Wilder writes with clarity and with cutting truth, providing a painfully beautiful atmosphere in which he examines the impossible balance of predestination, divine intention, divine abandonment, and divine indifference.

All I can hope is that I do not end up like Brother Juniper.

*****

This post is part of my 50 Classics in 5 Years series.